December 1901, Peking.

It was a frosty morning in Beijing. Before anyone wakes up for the day’s work, a kitchen stirs to life. As the first thread of smoke peeked out of the chimney, it was greeted by the blush of dawn.

Within the confines of the ancient royal walls, people have never imagined a life with water running from the tap. The Dragon Springs, emerging out of the limestone aquifers of the Xishan Hills, nourished the imperial city and near a million residents.

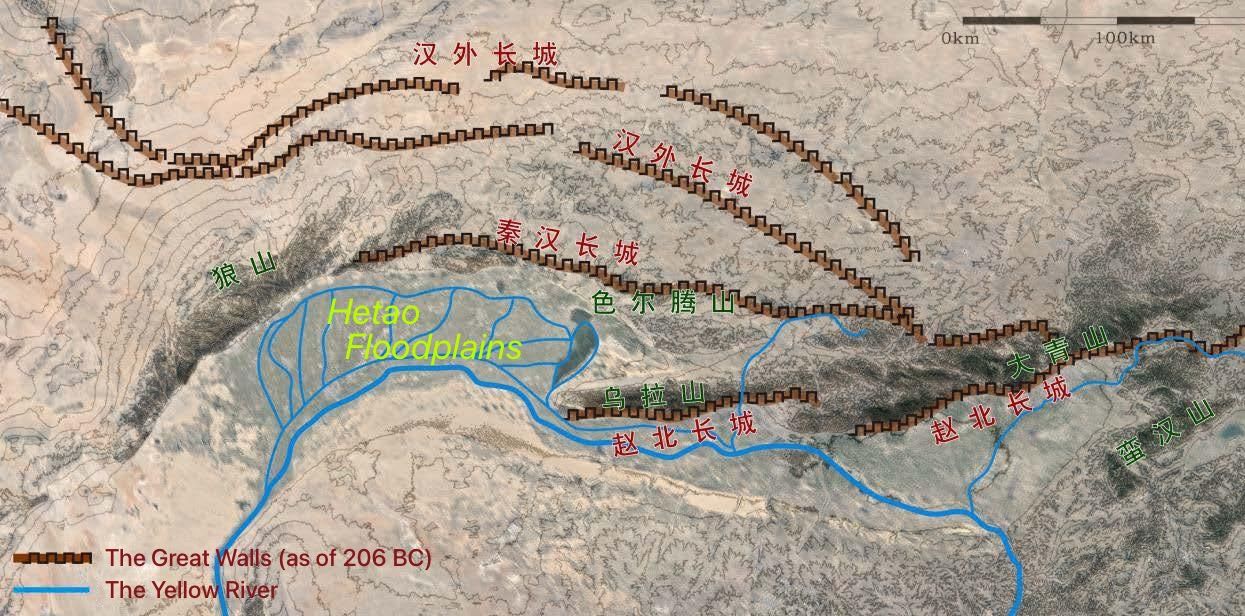

Flour dust swirls in the golden morning light, dancing in the air like the first flakes of winter. The pillowy texture demands nothing short of the finest, the Snow White flour. It is only made with winter crops from the Hetao Floodplains, a piece of land so fertile that generations of Mongolian calvalry risk their lives to scale the Great Wall.

Now back to what’s in front of us. On top of the fireplace sits a glazed terracotta bowl, covered by damp linen. The sourdough starter, or Laomian (‘Old Dough’) as we call it, produces flavour unmatched by dried yeast or leavening salts.

Between the cook’s seasoned hands, the dough suffers ten minutes of pushing and pulling, and folding onto itself. Under a clean cloth it now rests for its first proof, warming up and billowing as the starter is awakened by the fresh supply of starch.

The belly is the best cut butcher can offer. At a ratio of three parts fat to seven parts lean, it is firm enough on the first bite, but quickly melt in the mouth. Sichuan peppers, Shandong green onions, and the famous Shaoxing yellow wine provide a balancing force to the richness of the pork.

The dough, swelled with promise, is divided into little stubs. With a rolling pin made of rigid jujube wood1, the cook pushes on the edge of the stubs until it expands into a flap. He carefully avoided pushing into the centre, where a little thickness can help the Bao stand on its bottom.

- In Southern China people use wood from the papaya tree, known for its quality. ↩︎

He tugs the edge of the flap into itself, rotate, and repeat 18 times. What we have now is a delicate spiral — a crown of craftsmanship. Each flap of dough must be able to support its own weight in filling. Too much, the Bao will burst. Too little, Laoye (master of the house) won’t be impressed.

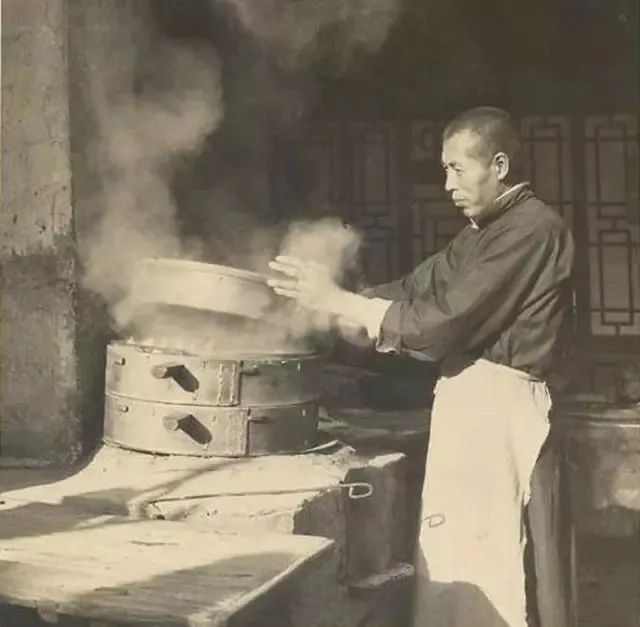

A bamboo steamer, fragrant with the souls of a thousand breakfasts before, is lined with parchment and filled with these plump parcels of meat. First in wisps, then in billows, the steam rises swirling around the Baos. The yeasts, in their last moment of lucidity, bestow their greatest gift of life in service to the Bao. The cook thinks of himself, four decades ago, walking into the House for the first time.

The maid arranges for a saucer on a lacquered mahogany tray. In the household of a Mandarin like Laoye, ceramics are supplied directly by the Yuqi Chang, the imperial kiln factory.

A dark, glossy pool of vinegar, brewed with millet, sorghum, along with charred barley malt for its caramel colour. Its sharp tang cutting through the warmth of the bao.

With a careful dip, the soft dough soaks up the bold flavours, the contrast of rich, juicy filling and bright, acidic sauce coming together in perfect harmony—each bite a balance of warmth, depth, and tradition.

This is the tale of a Bao — a poetry of patience, precision, and perfect proportion.

Copyright © 2025 Grandmaster Bao. Some rights reserved.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0) You may share and adapt this work for non-commercial purposes with proper attribution.